New results suggest that insecticide use in the tropics is to blame for the re-emergence of bed-bug infestations.

Exposure to treated bed nets and linens meant that populations of bed-bugs had become resistant to the chemicals used to kill them, researchers said.

The findings could help convince pest controllers to find alternative remedies to deal with the problem.

The results were presented at the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene’s 60th annual meeting.

Since almost vanishing from homes in industrialised countries in the 1950s, populations of the common bed-bug have become re-established in these regions over the past decade or so.

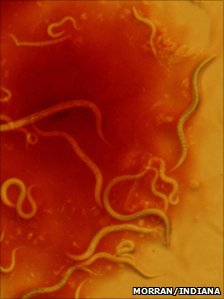

These mostly nocturnal feeders are difficult to control, not only because they are adept at avoiding detection by crawling into creases of soft furnishing but also because they have developed a resistance to many of the chemicals that have been used to kill them.

Findings presented at the gathering in Philadelphia showed that 90% of 66 populations sampled from 21 US states were resistant to a group of insecticides, known as pyrethroids, commonly used to kill unwanted bugs and flies.

One of the co-authors – evolutionary biologist Warren Booth, from North Caroline State University in Raleigh – explained that the genetic evidence he and his colleagues had collected showed that the bed-bugs infecting households in the US and Canada in the last decade were not domestic bed bugs, but imports.

“If bed-bugs emerged from local refugia, such as poultry farms, you would expect the bed-bugs to be genetically very similar to each other,” explained entomologist and co-author Coby Schal, also from North Carolina State University. “This isn’t what we found.”

In samples collected from across the eastern US, the team discovered populations of bed-bugs that were genetically very diverse.

This suggested that the bugs originated from elsewhere, and relatively recently because the different populations had not had time to interbreed, Dr Schal explained.

He suggested that the source for the new outbreaks was warmer climes, where the creatures would have probably developed a resistance to chemicals.

“The obvious answer is the tropics, where they have used treated bed nets [and] high levels of insecticides on clothing and bedding to protect the military,” Dr Booth told BBC News.

He explained that although bed-bugs were essentially eradicated from industrialised countries in the 1950s, they continued to thrive in Africa and Asia.

“Its very likely that it is from one of these areas where insecticide resistance evolved,” he said.

‘Home-grown’

However, UK-based pest management specialist Clive Boase questioned that hypothesis.

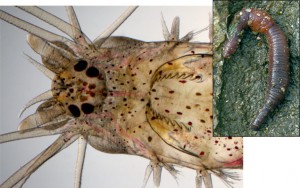

He said bed nets, to protect against mosquito-transmitted malaria and dengue, were only used in parts of Africa that were hot, where the tropical bed-bug (Cimex hemipterus) was found.

But, he added, it was not the tropical bed-bug that was the problem in the US and UK; instead it was their temperate cousin, Cimex lectularius.

Dr Boase explained that comprehensive records showed that infestations of bed-bugs in Europe were less pervasive in the 1970s and 80s, but they were still present.

By continually exposing these populations to insecticides, which came on the market in the late 1970s, these creatures likely developed resistance, he said.

“We don’t have to invoke stories of disease control programmes in Africa; all the evidence here in the UK is that our problem is home-grown.”

Dr Boase wondered that if the US had similar long-term records whether the researchers would have reached a different conclusion.

Evolutionary biologist Richard Naylor from the University of Sheffield agreed: “I am kind of surprised by [their interpretation].

“It doesn’t seem that difficult to develop resistance or lose it; in lab cultures, if you stop exposing [bed-bugs] to pyrethroids it drops out of lab populations very quickly,” he said.

Mr Naylor asked that if the US bed bugs had been exposed to the chemicals elsewhere in the past, “why would they still be resistant?”

:: Read Original here ::